David Pick | Nr. 63

Bis vor Kurzem noch dem Untergang geweiht | David Pick über die enttäuschende Saison seines einstigen EuroLeague-Favoriten Olimpia Mailand.

How would you describe success? Is success measured by results? In a sports driven industry everyone is chasing wins. Naturally, winning and losing are what defines success. LeBron James pursues the number of rings Kobe Bryant has; Kobe Bryant chased the number of rings Michael Jordan has, and it becomes a never ending cycle of winning. For 99% of the industry, that’s how sports actually should be. No one remembers 2nd place.

EuroLeague glory doesn’t come from finishing 10th or 4th. You must win. Winning is addicting. Winning is the cure to losing. But for that small 1% percent, winning is defined in ways other than who put up more points on the scoreboard.

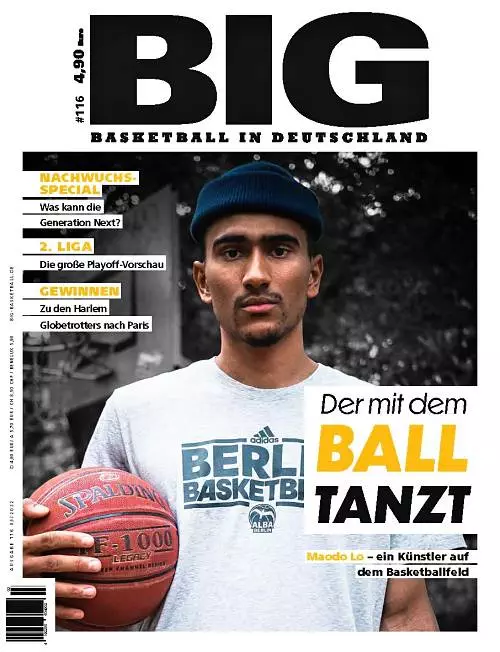

Take ALBA BERLIN for example: „winning“ for them is to develop more EuroLeague and NBA players. Obviously the German BBL competition can’t be taken lightly, but coaches aren’t getting fired nor are players getting cut after EuroLeague loses. Bayern Munich shares a similar, but a bit more ambitious EuroLeague approach, naturally, due to the older brother on the soccer pitch.

For other clubs winning is EVERYTHING. For Olimpia Milano, winning is EVERYTHING. Even before the Ettore Messia regime. I was in Milano for the 2014 EuroLeague Playoffs and Final Four, amid Luca Banchi’s quest to kick out Maccabi Tel Aviv. Keith Langford, Daniel Hackett, Nicolo Melli, Curtis Jerrells, Samardo Samuels, Gani Lawal … that team was built to WIN. Fast forward almost a decade later, the DNA hasn’t changed, the dollars are still poured in millions, and the results are the same.

Playing for Milano was, and still is, an Italian dream. It should be a career-goal. But the identity of the club is still a win-above-all DNA, and it shadows creating growth and success in grooming a local hero. Hackett, Melli, Allesandro Gentile, Simone Fontecchio were all unsatisfied, bolted overseas and found success.

The situation at Maccabi, another club struggling to find success in the form of international hardware, isn’t so different. Tel Aviv always overpaid Israelis to lure them from signing with Winner League rivals. Coaches play musical chairs, and imports come and go. It’s a goal for all Israelis to play for Maccabi, but only a rarity find success e.g. Guy Pnini and Yogev Ohayon, plus the current rise of Roman Sorkin.

It’s one thing to be a EuroLeague player. It’s another thing to play in the EuroLeague. Iftach Ziv, Rafi Menco and even retired PG Gal Mekel know that difference all too well. Tamir Blatt joined ALBA BERLIN, and Yam Madar moved to Belgrade. Yovel Zoosman blossomed into a EuroLeague wingman in Tel Aviv, but felt underappreciated, similar to the Italian stars, are left. Maccabi sent Dragan Bender and Dani Avdija to the NBA as Top-10 draft picks, making hundreds of thousands of dollars in buyout, so there’s a different form of “success”.

If the measurement of success was only „winning“ what does that make of Ergin Ataman now?! For the past two seasons he was crowned the KING of Europe, and spoke of NBA teams in the breath. Anadolu Efes are currently out of the playoffs. Does that make Ataman any less of a coach than before?! I doubt it, but others will argue.

Ettore Messina in his wildest dreams never envisioned carrying the entire EuroLeague on his back. In theory, the playoffs are still in reach, but it’s been an injury-plagued season which makes a late comeback even more challenging. My belief remains that no one would want to get Milano in a series, because they’ll be rolling and could build on that momentum all the way to the Final Four. Consider Milano, if they secure a Top-8 ticket, a dark horse in these playoffs.

If I’m not mistaken, I think I ranked them 1st on my preseason power-rankings board, so it’s fair to say all this is kinda awkward for me. But the writing was on the wall. Naz Mitrou-Long is not a PG. Devon Hall is not a PG. Billy Baron is not a PG, and Kevin Pangos was sidelined from round 10, while Shabazz Napier arrived on round 22 (!).

Up until a short while ago, like a really short while ago – not even an entire month ago – Giorgio Armani’s basketball club seemed doomed. Milano was on a 5-game losing streak, and the team was crushed. Even Varese’s high-tempo, up-and-down, shooting 3s, a-la Houston Rockets and Golden State schemes seem to flow better in modern hoop than the reserve, political, systematic, old-school basketball.

Messina is a former EuroLeague champion. Kyle Hines is a living legend. Baron arrived as a VTB-League winner with Zenit Saint Petersburg – none of them are about this losing life. Messina’s basketball has little room for error. He anchored his system around ONE (tall) floor general from Antoine Rigaudeau at Virtus, to Pablo Prigioni with Real Madrid, to Teo Papaloukas in Moscow; and finally Sergio Rodriguez in the Italian fashion capital. He never played with two PGs (a-la Gregg Popovich with Tony Parker).

Until Napier’s recent arrival, neither of the guards are Messina’s style of players. Napier too; he’s actually the opposite of what the coach likes. The entire season Milano was playing without a PG, and it’s visible now how impactful today’s basketball is playing with or without a point guard. Maccabi struggled without Wade Baldwin and then Lorenzo Brown, but thrived with both. Anadolu Efes looked clueless without Shane Larkin and are falling amid Vasilije Micic’s absence. Even ASVEL had a FIBA Champions League backcourt before inking Dee Bost (coming from a BCL club), which brought stability.

Circling back to the measurement of success. Messina took an Italian club and transformed its infrastructure, traveling conditions, and facilities to NBA standards. But that’s probably not a win. If winning is the be-all, end-all, Milano has (thus far) failed this season. Year I was good for Messina but the shortcoming of COVID-19 killed the season prematurely.

Year II for the first time in 29 years Milano returned to the EuroLeague Final Four, and came a shot away from the Final. Fatigue, load management, injuries and mental drain led to a sour 0-4 blowout loss against Virtus in the SerieA Finals.

Year III, Milano wins the Italian cup, and although they fell out of the EuroLeague in the series against back-to-back champions Anadolu Efes, the mental edge to compete was very much alive as Messina avenged Virtus and won the championship.

Year IV was plagued with injuries. That’s not disregarding how poorly the team was built and the money they poured on players. Shavon Shields‘ injury was tough, because he’s irreplaceable on the market, and Pangos being out diminished the lack of high level creation in the backcourt; the snowball kept rolling until recently.

Milano stormed back into the playoffs race, sporting a six-game win streak since acquiring Napier. It might be too little, too late, but to conclude the measurements of success: whoever says money can’t buy happiness, doesn’t know where to shop.